HIV and lung cancer may seem unrelated from a medical standpoint, but both conditions carry a stigma that can negatively impact patients and their access to treatment. However, insights gained from the HIV epidemic are now helping those affected by lung cancer and their families.

In the early years of the HIV crisis, misconceptions fueled discrimination and fear. Many believed the virus only affected men who have sex with men or that it could be transmitted through casual contact, such as sharing utensils. These false assumptions led to an atmosphere of blame, discouraging individuals from seeking testing or medical care.

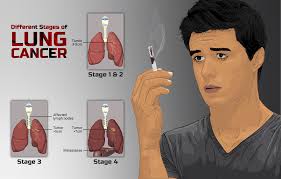

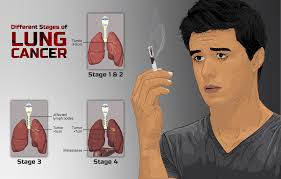

Similarly, people diagnosed with lung cancer often face judgment due to its well-known association with smoking, despite estimates from the National Cancer Institute indicating that 10–20% of lung cancer cases in the U.S. occur in non-smokers. As with HIV, this stigma can prevent individuals from pursuing medical attention when symptoms arise.

“Stigma is more than just a social issue—it’s a public health crisis,” says Marcus Wilson, Senior Director of U.S. Public Affairs, HIV Advocacy at Gilead. “It influences the quality of care people receive, whether they feel comfortable seeking help, and ultimately, their health outcomes.”

To address this issue, Gilead recently collaborated with GRYT Health to host a New Lens on Lung Cancer workshop, where individuals with lung cancer and their families shared their experiences with stigma.

Rhonda Meckstroth recalls how her husband, Jeff, who had no history of smoking, was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2015. “The first question was always, ‘Was he a smoker?’” she says. “We felt an immediate sense of shame and hesitated to specify that he had lung cancer when telling others about his diagnosis.”

Aurora Lucas, diagnosed at age 28, also encountered judgment. “People make assumptions about why you have lung cancer within seconds,” she explains. Some speculated her illness stemmed from working in a nail salon, while others wrongly linked it to building materials in her childhood home in the Philippines.

Just as the HIV community learned the importance of advocacy, those affected by lung cancer are realizing the need to stand up for themselves—both in society and in healthcare settings.

Jeff’s treatment took place in a rural medical system where doctors were not always up to date on the latest lung cancer research or clinical trials. They also didn’t consider risk factors beyond smoking.

“Because Jeff didn’t fit the typical lung cancer profile, his diagnosis was delayed by about six months,” Rhonda explains. “Instead of getting frustrated when people assumed he was a smoker, I started using those moments to educate others and place the responsibility where it belongs—on the tobacco industry.”

“We have so much to learn from the HIV community,” adds Jeff Stibelman, who was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2021 after an earlier scan in 2017 failed to detect it. “I remember seeing a billboard featuring a diverse group of people—different ages, ethnicities, and backgrounds. The message was simple: ‘This is what HIV looks like.’ That’s the kind of awareness we need for lung cancer.”

Aurora emphasizes the need to shift the narrative. “Anyone with lungs can develop lung cancer,” she says. “It’s time to stop the blame.”

In the early years of the HIV crisis, misconceptions fueled discrimination and fear. Many believed the virus only affected men who have sex with men or that it could be transmitted through casual contact, such as sharing utensils. These false assumptions led to an atmosphere of blame, discouraging individuals from seeking testing or medical care.

Similarly, people diagnosed with lung cancer often face judgment due to its well-known association with smoking, despite estimates from the National Cancer Institute indicating that 10–20% of lung cancer cases in the U.S. occur in non-smokers. As with HIV, this stigma can prevent individuals from pursuing medical attention when symptoms arise.

“Stigma is more than just a social issue—it’s a public health crisis,” says Marcus Wilson, Senior Director of U.S. Public Affairs, HIV Advocacy at Gilead. “It influences the quality of care people receive, whether they feel comfortable seeking help, and ultimately, their health outcomes.”

To address this issue, Gilead recently collaborated with GRYT Health to host a New Lens on Lung Cancer workshop, where individuals with lung cancer and their families shared their experiences with stigma.

Rhonda Meckstroth recalls how her husband, Jeff, who had no history of smoking, was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2015. “The first question was always, ‘Was he a smoker?’” she says. “We felt an immediate sense of shame and hesitated to specify that he had lung cancer when telling others about his diagnosis.”

Aurora Lucas, diagnosed at age 28, also encountered judgment. “People make assumptions about why you have lung cancer within seconds,” she explains. Some speculated her illness stemmed from working in a nail salon, while others wrongly linked it to building materials in her childhood home in the Philippines.

Just as the HIV community learned the importance of advocacy, those affected by lung cancer are realizing the need to stand up for themselves—both in society and in healthcare settings.

Jeff’s treatment took place in a rural medical system where doctors were not always up to date on the latest lung cancer research or clinical trials. They also didn’t consider risk factors beyond smoking.

“Because Jeff didn’t fit the typical lung cancer profile, his diagnosis was delayed by about six months,” Rhonda explains. “Instead of getting frustrated when people assumed he was a smoker, I started using those moments to educate others and place the responsibility where it belongs—on the tobacco industry.”

“We have so much to learn from the HIV community,” adds Jeff Stibelman, who was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2021 after an earlier scan in 2017 failed to detect it. “I remember seeing a billboard featuring a diverse group of people—different ages, ethnicities, and backgrounds. The message was simple: ‘This is what HIV looks like.’ That’s the kind of awareness we need for lung cancer.”

Aurora emphasizes the need to shift the narrative. “Anyone with lungs can develop lung cancer,” she says. “It’s time to stop the blame.”

Breaking the Stigma: Lessons from HIV Helping Lung Cancer Patients

Breaking the Stigma: Lessons from HIV Helping Lung Cancer Patients

Companies

Companies